This essay was originally published on Medium on 10 April 2020.

Since the second week of the lock-down in the UK, when I recovered from a suspected but untested case of coronavirus, I have been wondering about the best word to describe what I am feeling. There are individual words for describing parts of the experience — a general feeling of malaise, horror at seeing the number of dead creep up, anxiety for vulnerable friends and family, cabin fever — but there is something missing. Nostalgia for the recent past does not feel quite appropriate, because life before still seems within grasp and possible to return to. Wistfulness for the days when one only worried about hand-washing does not capture the heart-wrenching quality of the experience. I keep coming back to the idea that what I am feeling is closest to homesickness, even though, perversely, I am actually locked into my home.

Even if I do manage to put words to it, this experience will still be different from anything we have seen. Because it is not just individual coronavirus patients who have been ill. We are experiencing illness collectively, as a society.

In her brilliant book on the Phenomenology Of Illness, philosopher Havi Carel makes the distinction between disease and illness. Disease is biological dysfunction; illness is the experience of having a dysfunctional body. Someone might have the disease of cancer, but if they are not aware of it, they do not have the experience of illness. Equally, some argue that mental illness makes people feel ill, while we are so far unable to clearly identify the underlying disease. Maybe love-sickness is a better example. The overwhelming feelings at the end of a relationship can make us feel unwell, but we are not in fact suffering from bodily disease. Thus even if we have not all been infected with coronavirus as a disease, or have weathered it without symptoms, we as a society suffer from the illness of coronavirus together.

What does it look like to be ill communally, as a society?

In her work Carel draws on Toomb’s characterisation of illness. Toombs argued that all types of illness can be described as five kinds of losses. The first of these is loss of wholeness. It threatens not just our functioning as a society but also our understanding of who we are as a society. We want to prioritise lives saved and fretting about the state of the economy makes us feel guilty. We want to come together and support each other, but social distancing, family and work commitments are pulling us apart. This is also reflected in the questions we ask ourselves about the kind of world we will return to when the pandemic is over.

This loss also reflects what Carel calls loss of transparency. In illness we start to notice the things that are normally invisible or transparent to us. We might find it hard to breathe, to walk, to get out of bed, to think clearly. Now it is our social and economic interactions that have lost their transparency. Chatting to neighbours, seeing friends and family, going to work, taking public transport, buying groceries, even keeping our jobs are things we are noticing and we notice with wonder how easy and straightforward these things were just a few short weeks ago.

The second characteristic of illness is loss of certainty. We haven’t quite planned for this. We have suddenly lost many things we have taken for granted: some of our freedom, much of our self-understanding. We no longer feel autonomous and self-governing quite like we did at the start of this year. There is now something bigger, meaner than us in our way, blocking our path towards who we want to be and what we want to do. We are starting to realise that we have never quite been autonomous the way we have believed ourselves to be.

The third is loss of control. We no longer make some of the really big decisions for ourselves. Our governments tell us to stay at home and we cannot even take comfort in accusing them of authoritarianism. Many do not have a choice who they are locked down together with: whether that’s an annoying housemate, unsympathetic parents or an abusive partner. Many have lost their jobs and lost control of their finances. Those key workers who have to go out to work, but would rather not, have also lost control: the right to say no. Just like ill people do, as a society we look to scientists, doctors and nurses to save us and we are happy to relinquish control to them.

The fourth is loss of freedom to act. We are all feeling this right now in big and small ways. I am desperate to visit my mother in Hungary, who is currently undergoing chemotherapy, but I cannot. I would like to drive down to the coast for a long walk, but I am not allowed. I would love to quickly run into the supermarket for a bottle of milk, but I must not, I have to queue up.

The fifth is loss of the everyday world. Paraphrasing Toombs, Carel says this “arises from the disharmony illness causes and its distinct mode of being in the world. The ill person can no longer continue with normal activities, or participate in the world of work and play as before.” The twist this time is that our family, friends, colleagues and neighbours are also in the same situation. We are experiencing the loss of our everyday world communally, even globally.

This is probably my strongest experience right now and captures what I have been clumsily groping at when I talked about homesickness. I miss my normal environment, my neighbourhood, my usual haunts, but not because I have been dislocated in space. It feels as if it should be easy to return to normal, but it isn’t. Sometimes one is homesick, but cannot get on a plane or train and travel home or at least not for a few weeks or months yet. This extended feeling of homesickness also captures that when one does finally get to go home after an extended absence, things are no longer the same. The builders have finished the house round the corner. A local shop has closed and a new business opened in its place. Friends’ children are taller. Time does not stand still just because we are not there to witness changes. It is the same now. Even when lock-down ends, even when a vaccine for coronavirus is finally available, things will have changed in big and small ways.

The coronavirus pandemic also shows our extreme interconnectedness. Someone eats some dodgy wild animal meat at the other side of the world and now I am not allowed to go to the garden centre because I might inadvertently infect and kill someone living in the next town. This is not just a function of globalisation. Globalisation might make the spread of the disease faster and geographically wider, but this social interconnectedness applies even to small communities, even at ordinary times. This pandemic affects us on all levels: as individuals, as families, as local, national and global communities. As David Kessler has argued, right now even our grief is collective in a way which we are not used to.

Thinking of the pandemic as a global illness of society is useful because it allows us to think differently about our reactions and about what it is going to be like when all this is over.

If everyone is experiencing this illness, even if they do not have the disease, we might look at each other’s reactions more forgivingly. We all have our bugbears right now. The neighbour who is suddenly irritated by any noise we make. All those people who recommend that we should use this time for self-improvement: learning to play that Bach piano piece, reading Proust, gardening, taking up a new hobby, running a marathon on the balcony. The people who are irritating enough to actually run a marathon on the balcony and read Proust. The people who just want to sleep until all this is over and let their children watch tv all day. People who hope that this illness will show that everyone is equal. People who still think that personal courage and fortitude can help us fight off diseases. Whether it is denial, apathy, self-delusion or wishful thinking, these can all be normal responses to an experience of illness. Feeling empathy and showing forgiveness does not mean we should not question the reactions of others, just that we should do so kindly and with understanding.

Adopting this attitude can also make us more forgiving to those who are in denial or angry.

The former might break the lock-down to go sunbathing in the park. Some vulnerable people who should be self-isolating still go out to the shops. The latter might be angry because the garden centre is closed just at a time when we are all stuck at home and the weather is glorious. These are all individual responses to our illness experience. We need not approve of them, but we need to learn to approach them with sympathy.

The invisibility of the coronavirus also leads to cognitive dissonance: it can be hard for us to grasp how dire the situation is when there are no bombs falling from the sky, no earthquake ruins to comb for survivors, corpses and possessions. There are no crosses painted on the boarded up houses of those infected, as there were during the 17th century plague epidemics. The virus itself is not visible to the naked eye. Those moderately ill are self-isolating. Those seriously ill are shut away in hospitals and ICUs. The numbers are by now so large that we can no longer make meaningful emotional sense of them. Why should it then be surprising that some of us over-react by panic buying while others under-react? Humans are not fully rational decision-makers, we are not equipped to all react to this situation in an ideal way.

My work on democratic theory and social and political philosophy also makes me think of the best ethical reaction to the pandemic in politics and civil society. There are the obvious points: governments should not use this as an opportunity to extend powers towards authoritarianism as the government in Hungary has done. Lock-down is not an excuse for moving towards or cementing a totalitarian police state. Transparency and accountability in decision-making and the execution of those decisions is more important than ever. As citizens of democratic countries, we need to know who is in charge when the prime minister is in hospital, how decisions are made about imposing restrictions on our freedom, why the police stops and fines people for leaving their houses. This can only be achieved if legitimacy, another key property of democratic government, is met. When things fall apart, the already shaky concept of representation becomes even harder to define. Should our representatives do exactly what we want them to do right now? Should they decide more independently, knowing that we will trust them to have their best interests at heart? Would it be better if the government was headed by someone who has actually experienced what it is like to be in ICU with coronavirus?

The pandemic also makes us examine some difficult questions about whom to prioritise in times of crisis. Should countries focus on their own citizens and residents, even to the point of blocking the export of crucial supplies? How shall we strike the balance between looking after our own and global cooperation? There is a sudden realisation that yes, medical care has to be rationed and we do have rules for how to do this. This doesn’t just happen when ICUs are full to capacity and running out of ventilators. Scarce resources like organs have to rationed all the time. These are problems that philosophers, scientists and policy makers have had to think hard about for decades, but are not usually part of public awareness.

The pandemic also brings to the fore some of the structural injustices which are all too easy to ignore.

Because we are not all equally in this together. Social distancing is not the same for everyone. Some people have gardens, others are stuck in tiny, airless flats. Women, once again, are affected disproportionately by lock-down measures, as most of the extra childcare and homeschooling falls to them. They also have to go out and work in disproportionate numbers in relatively low paying jobs, as nurses, teachers, cleaners or supermarket staff. There seem to be clear evidence that poorer people and BAME (black and ethnic minority) people are more likely to be badly affected by the infection both in the US and the UK. And I haven’t even started on global inequalities yet.

My hope is that once this crisis is over, we will learn some lessons from the pandemic. I also wish that we could have learned all of this in a more gentle way.As our societies and us, as members of those societies, have been ill in a sense, hopefully we will learn to be more empathetic and forgiving towards each other and especially those who are ill and disabled. As citizens we might learn to think more clearly about the values we want our democratic governments to have and work to maintain them. Hopefully we will not let structural injustices retreat once again into the background or even worsen, but strive to understand how inequality and exclusion affect others and work to eliminate them. None of this means that the pandemic is good because it helps us towards deeper meaning in life. The pandemic is very bad indeed, but some of the lessons we learn from it might be good.

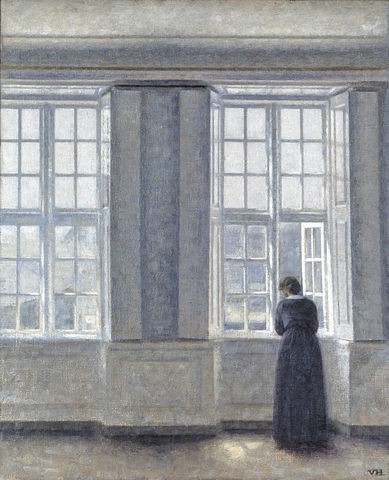

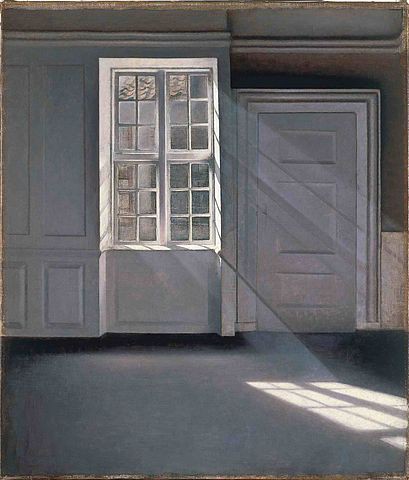

I am grateful to CBeebies and Peter Rabbit for making it possible to write this piece during my daughter’s screen time, Vilhelm Hammershoi for his beautiful, haunting paintings of loneliness and alienation (via Wikimedia Commons) and Gerald Chappell, Claire Dunn and Laura McIntyre for their helpful feedback.